Christopher Cowell, who describes himself as “an architect and accidental academic”, is a fan of alliteration. He has now written his first book, which is called . The title is a winking reference to American architect Louis Sullivan, who famously declared, in an 1896 essay, that “form follows function”.

In this case, the prime mover is health. Cowell’s subtitle is ; and although he states in his introduction that it is not his intention “to pin an entire city creation story and its urban morphology upon the presence of malaria”, it is clearly a useful peg on which to hang a new version of an old tale. The malaria of the title is probably not malaria as we understand it today.

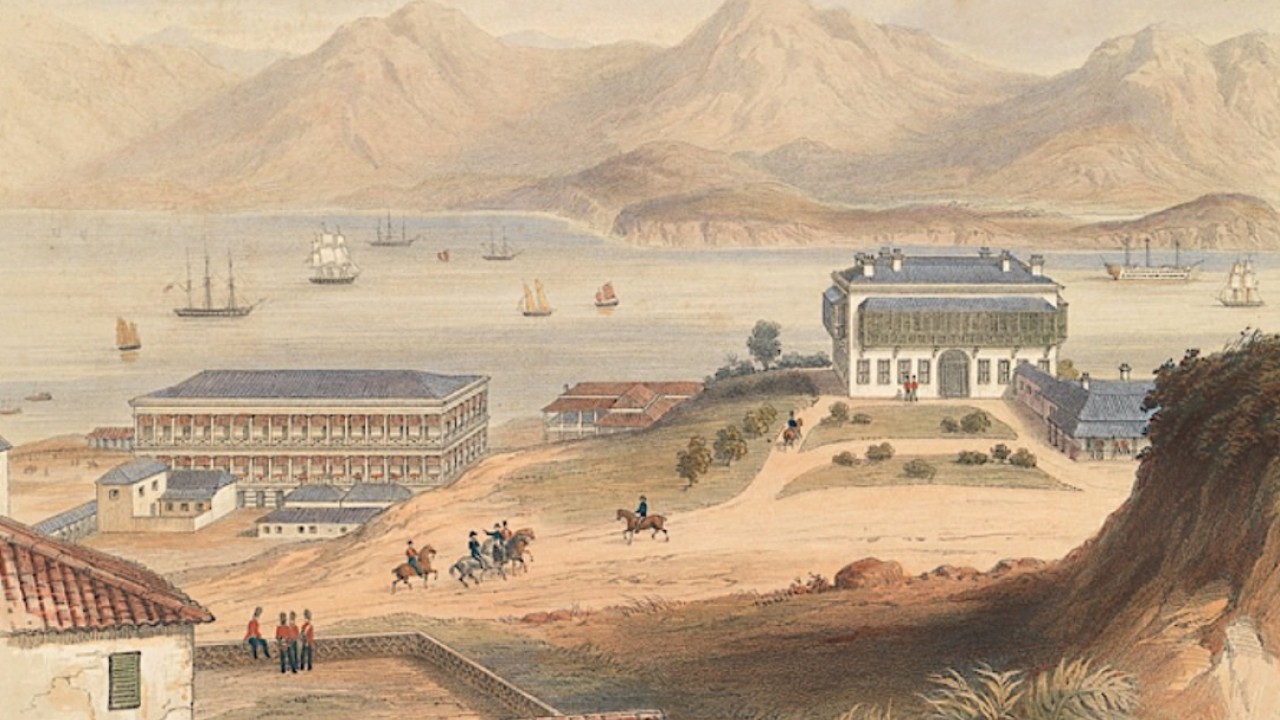

In fact, apart from a few official medical references, people at the time rarely used that word. In 1843, when the city – really more of a ramshackle town – was blighted by illness, it became known by the catch-all “Hongkong Fever”; in 1848, it was called “barrack fever”. “‘Marsh miasma’ was another term,” agrees Cowell, cheerfully.

“It was ‘bad air’, which is what means. “The interest for me is not what it is, it’s that it had a strange agency. It threw itself into the planning of Hong Kong and disrupted it.

” Today’s residents may like to know that even then, the local population found the south side of the island more salubrious. Elliot had arrived in January, a dry, cold month. As the winds and weather shifted, however, sickness set in.

By August 1842, .