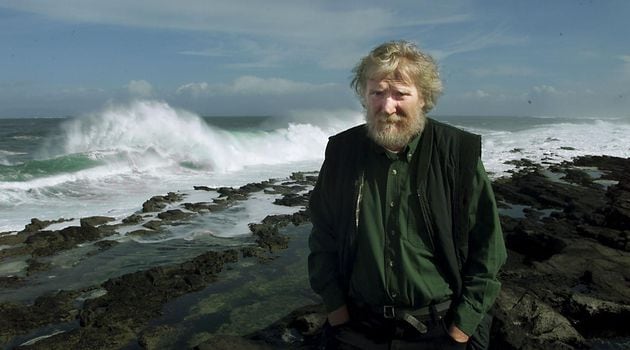

It is late June 2024 in Ballyconnell, north Sligo , where the greening of the reedbeds is in full sway. The constant showers, punctuated by intense, brief bursts of heat, have brought forth dazzling clumps of fluffy white bog cotton the size of summer clouds. In the luminous salty spray swept inland from the white-capped sea, it takes a moment to resolve the contours of the coastal cottage where the writer Dermot Healy with his partner Helen set up house in the early 1990s.

A dwelling so close to the Atlantic, it might be a small craft pointed into the waves. Above a pebbly beach with grey sand, the marram grass holds fast to the embankment alongside the laneway to the cottage and its outbuildings. The packed clay, sand and stones of the embankment are bolstered by strategically placed wire cages filled with rocks.

The configuration and embedding of these coastal-erosion-preventing boxes, or gabions to give them their proper name, were decided only after Dermot’s meticulous, daily observations of the swirls and sluicing movements of incoming and outgoing tides, and the most vulnerable points of encroachment during high seas and storm surges. In Dermot and Helen’s time, the gabions that kept the sea back from their property needed regular maintenance. And Dermot routinely arrived on the strand to issue instructions to a local digger-man teamed with his brother, there to gather and pack stones into the hungry maw of the gabions that came in the form of flat-packs.

Dermot wa.